When you are starting to work on your opening titles,

you might want to organize the credit information you receive from the

client and begin a rough sketch of how the titles will unfold over time

(also called animatics). The following terminology and concepts will

help you organize your work and facilitate the communication between you

and your client. When we talk about a title card, we refer to a screen

that displays the credit information of the cast and/or crew. Titles and

title cards can be distinguished as follows:

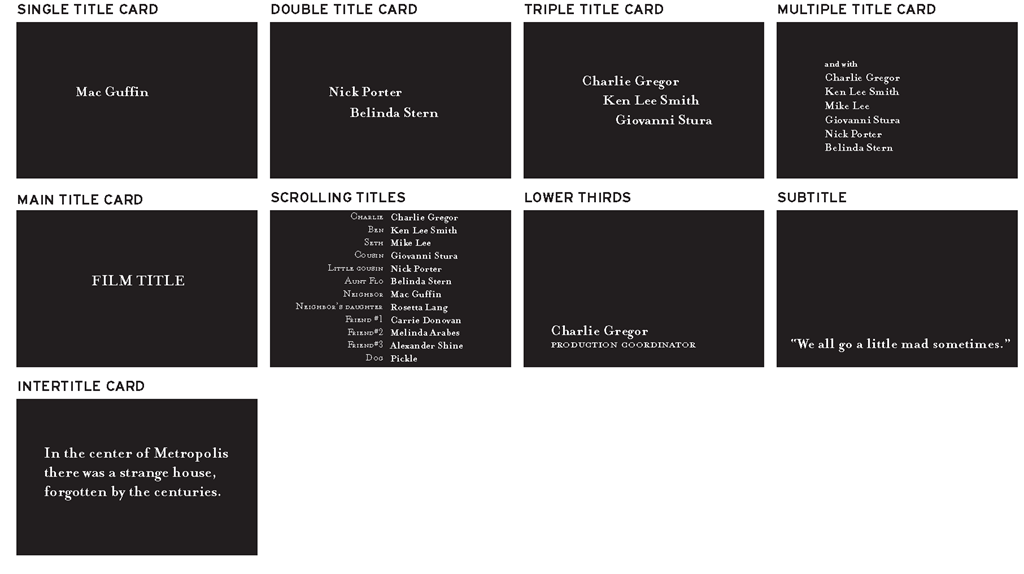

• A single title card contains one name credit. A

single title card is typically used in opening titles to display the

name of the lead actors and the creative people involved in the movie

(director, producers, writer, cinematographer, composer). These are

generally referred to as the above-the-line credits.

• A double title card contains two name credits. A double title card typically is used to display the names of supporting actors and additional creative people involved in the movie.

• A triple title card contains three name credits. A triple title card is typically used to display the names of additional supporting actors.

• A multiple title card contains more than three name credits. A multiple title card is typically used to name additional supporting actors or extras.

• A main title card displays the main title of the movie.

• Scrolling titles are titles that move sequentially in and out of frame, generally used as end titles. End scrolling titles usually repeat the credits of the opening titles (the talent credits of the opening titles are reorganized either in order of appearance or alphabetically) and then display the below-the-line full crew and cast credits: the special effects, props, soundtrack, equipment and location rentals, film stock, and so on. A title designer can create the design and layout of the text blocks, but if digital scrolling titles are needed (as opposed to a film-out), some companies in Hollywood specialize in digital scrolling titles that avoid flickering type and look nice and smooth.

• A lower third is a title placed on the lower-third of the screen (although there might be other screen placements you could consider), generally used to display the information—name and title—of a person being interviewed or a location.

• Subtitles are titles placed on the lower-third part of the screen (or sometimes on the top of the screen to avoid covering relevant information on-screen or previously existing lower thirds). These are generally used to translate dialogue in another language.

• Intertitles are title cards that display the time, place, prologue, or quotes. In silent films, an intertitle is often used to convey minimal dialogue or information that can’t be deduced from the talent’s body language or the scene’s settings.

Figure 1.3 Title card examples.

Depending on the type of movie you are working with (home movie, independent flick, Hollywood movie, or something else), the order in which the credits in opening and closing titles appear on-screen and their font size, especially in large-budget productions, are greatly determined by the talent’s contracts, union contracts, and industry conventions. The designer will have very little (if any) say in that. For example, a clause in a talent’s contract might dictate that his credit shouldn’t be in a smaller font size than the one of the main title card. A different clause in another talent’s contract might dictate that her title card be the first one, regardless of who else acts in the film.

Also, depending on the film’s domestic and international distribution, you might have to composite different studio logos at the head of your title sequence. Or you might even have to deliver a version of your title sequence without any text so that English titles can be replaced by titles in another language.

As you’re approaching designing a title sequence, you should obtain any pertinent information about the talent or distribution contracts that might affect the title cards’ order or text size.

• Ask the client to give you a digital file containing the typed credits of the movie, with numbered title cards. For example:

1. XYZ logo

2. ABC logo

3. DFG production presents

4. A film by First Name Last Name

5. With First Name Last Name

6. And First Name Last Name … and so on.

• Avoid typing anything else; use only the typed information with which you’ve been provided.

• Copy and paste the names from the file the client provided you with into the software you’re using to create the title cards.

• Check the titles often for accidental letters you might have inserted from using common keyboard shortcuts (for example, in Illustrator, watch out for extra f’s from using the Type tool or i/’s from using the Selection tool). When you are pasting your title card text in your software and then pressing a keyboard shortcut, it’s possible that instead of changing to a different tool you are actually typing an unwanted letter in the text box.

• When you’re ready to show your title cards to your client, send the actual stills of your project file for review. Don’t send an early version or alternate versions; simply send the stills taken from the latest version of the actual project you are working on. There are a number of quick ways to accomplish this task. You could take a snapshot of the title cards directly from the software interface or from your rendered QuickTime file, or you could even export a digital still frame from your software and then email or fax it to your client for approval.

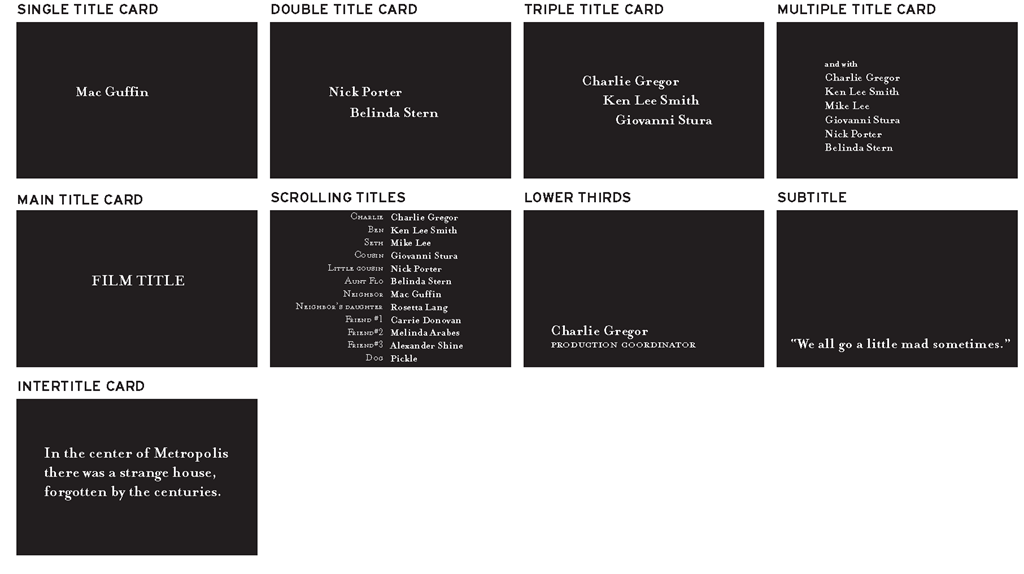

• A double title card contains two name credits. A double title card typically is used to display the names of supporting actors and additional creative people involved in the movie.

• A triple title card contains three name credits. A triple title card is typically used to display the names of additional supporting actors.

• A multiple title card contains more than three name credits. A multiple title card is typically used to name additional supporting actors or extras.

• A main title card displays the main title of the movie.

• Scrolling titles are titles that move sequentially in and out of frame, generally used as end titles. End scrolling titles usually repeat the credits of the opening titles (the talent credits of the opening titles are reorganized either in order of appearance or alphabetically) and then display the below-the-line full crew and cast credits: the special effects, props, soundtrack, equipment and location rentals, film stock, and so on. A title designer can create the design and layout of the text blocks, but if digital scrolling titles are needed (as opposed to a film-out), some companies in Hollywood specialize in digital scrolling titles that avoid flickering type and look nice and smooth.

• A lower third is a title placed on the lower-third of the screen (although there might be other screen placements you could consider), generally used to display the information—name and title—of a person being interviewed or a location.

• Subtitles are titles placed on the lower-third part of the screen (or sometimes on the top of the screen to avoid covering relevant information on-screen or previously existing lower thirds). These are generally used to translate dialogue in another language.

• Intertitles are title cards that display the time, place, prologue, or quotes. In silent films, an intertitle is often used to convey minimal dialogue or information that can’t be deduced from the talent’s body language or the scene’s settings.

Figure 1.3 Title card examples.

Depending on the type of movie you are working with (home movie, independent flick, Hollywood movie, or something else), the order in which the credits in opening and closing titles appear on-screen and their font size, especially in large-budget productions, are greatly determined by the talent’s contracts, union contracts, and industry conventions. The designer will have very little (if any) say in that. For example, a clause in a talent’s contract might dictate that his credit shouldn’t be in a smaller font size than the one of the main title card. A different clause in another talent’s contract might dictate that her title card be the first one, regardless of who else acts in the film.

Also, depending on the film’s domestic and international distribution, you might have to composite different studio logos at the head of your title sequence. Or you might even have to deliver a version of your title sequence without any text so that English titles can be replaced by titles in another language.

As you’re approaching designing a title sequence, you should obtain any pertinent information about the talent or distribution contracts that might affect the title cards’ order or text size.

Avoiding Typos

Typos are the one mistake you want to avoid while working on a title sequence. After you worked long and hard on a film or a TV show, would you want your name to be spelled wrong? I don’t think so. The following are a series of tips that will help you avoid a number of headaches and keep your clients happy.• Ask the client to give you a digital file containing the typed credits of the movie, with numbered title cards. For example:

1. XYZ logo

2. ABC logo

3. DFG production presents

4. A film by First Name Last Name

5. With First Name Last Name

6. And First Name Last Name … and so on.

• Avoid typing anything else; use only the typed information with which you’ve been provided.

• Copy and paste the names from the file the client provided you with into the software you’re using to create the title cards.

• Check the titles often for accidental letters you might have inserted from using common keyboard shortcuts (for example, in Illustrator, watch out for extra f’s from using the Type tool or i/’s from using the Selection tool). When you are pasting your title card text in your software and then pressing a keyboard shortcut, it’s possible that instead of changing to a different tool you are actually typing an unwanted letter in the text box.

• When you’re ready to show your title cards to your client, send the actual stills of your project file for review. Don’t send an early version or alternate versions; simply send the stills taken from the latest version of the actual project you are working on. There are a number of quick ways to accomplish this task. You could take a snapshot of the title cards directly from the software interface or from your rendered QuickTime file, or you could even export a digital still frame from your software and then email or fax it to your client for approval.